December 22, 2022 – Tybee lost 25 feet of shoreline to Hurricane Ian. What data tells us about beach erosion.

Improved dune system mitigated some of storm’s effects.

Nancy Guan

Savannah Morning News

Link available for Savannah Morning News subscribers here

The Georgia coast had a near miss when Hurricane Ian tracked further east than initially forecasted in September, but that doesn’t mean the coastline was spared from the storm’s impacts, new data shows.

Tybee Island’s beach saw significant erosion as high tides and strong waves wrought by Ian’s storm-force winds lapped at the barrier island’s sandy shores. From the single incident, Tybee’s shoreline receded by an average of 25 feet, according to data from the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography.

More:’A nothing-burger’: Tybee draws surfers, winds and curious tourists after Ian skirts coast

“That’s roughly a typical year’s worth of erosion based on our data,” said Clark Alexander, director and professor at Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, which began monitoring Tybee’s beach erosion in March 2020. “This is the first time (in the 2.5 years) we had a storm that had a measurable impact on the beach profile.”

However, that doesn’t mean Tybeeans need to be “running around with their hair on fire.” The good news, Alexander points out, is that Tybee’s beach renourishment projects and dune fortification system are working.

Regular beach renourishment projects, where sand is pumped onto the beach from an offshore site, have fortified Tybee’s shores since 1976. In the most recent renourishment, completed in 2020, the city also invested about $2.6 million into filling in the gaps of its dune system. The dunes play a major role in trapping and retaining sand, especially during this past hurricane season.

More:Tybee’s beach grows wider

In-depth:As Tybee Island’s federal contract for beach renourishment ends, officials look to what’s next

How the dunes protect the beach, reduce flooding

While the beach surface closer to the water lost sand over the last 2.5 years, the dunes and sand fencing that sit farther inland were able to capture about half of the volume lost. Dunes not only help retain sand but also serve as a storm barrier to homes and structures on the island, mitigating flooding. The sandy mounds also serve as habitats to a variety of wildlife, making them an important part of the ecosystem as well.

Some of the lost sand may also re-deposit onto the beach in the summer due to the natural, seasonal movement of the waves, said Alexander. In the winter, when wave activity is stronger, shores tend to erode. But during the summer, when there’s less energetic wave activity, sand gets moved back onto the beach.

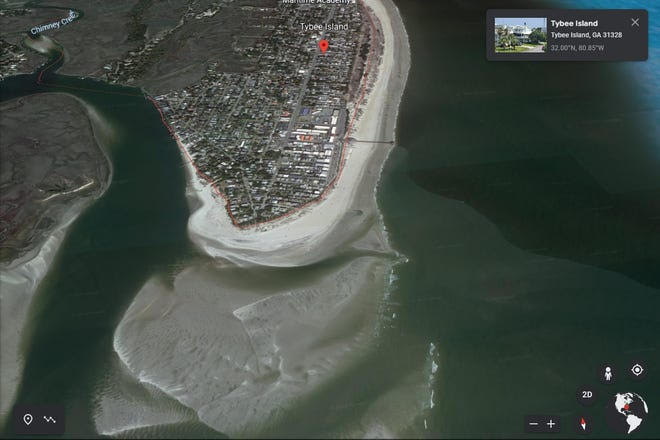

A closer look at the data shows that not all parts of the shoreline are affected equally, which largely has to do with the north-south direction of Tybee’s dominant winds as well as the natural movement of the waves. Because Tybee winds come frequently from the northeast, sand tends to accumulate at the south end of the island, resulting in what is called an ebb tidal delta at the mouth of Tybee Creek, more colloquially known as the back river.

This southward movement of sand, also known as longshore transport, is interrupted by activity in the Savannah River channel. A USACE study found that expansion of the channel to accommodate larger cargo ships calling on the Port of Savannah, was responsible for 70% to 80% of erosion to the Tybee Island shelf and shoreline. Another study is being done on ship wake impacts on Tybee’s shoreline as well.

More:Tybee’s priceless sand: Regular beach renourishments curb erosion, protect local economy

More:After 20-plus years, Savannah Harbor Expansion Project is complete, more growth planned

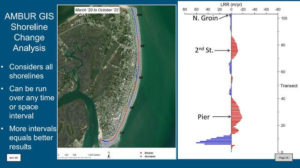

As waves hit the shore, pushing and shifting the sediment, some areas actually grow wider, while others recede. Historically, Tybee’s mid-section has remained relatively stable. Meanwhile, 2nd Street on the north end and the area around the pier towards the south typically see the most erosion.

Overall, the institute’s data shows that Tybee’s 3.5-mile long shoreline has receded an average of 7.7 feet every year.

Average coastline recession rates of 25 feet per year are not uncommon on some barrier islands in the Southeast, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In undeveloped areas, that might not be as much of a concern, but in populated areas, such as Tybee, the shoreline is a crucial form of protection.

“We want to be able to tell the city how things are changing, and tell them where they might experience erosion problems sooner rather than later, so they can plan to address them in a proactive way,” said Alexander.

Pictures shown: Tybee Island beach in 2019 before beach renourishment vs. in 2020 after renourishment. (Courtesy of Alan Robertson AWR Strategic Consulting)

More:Tybee prepares for long-term solutions to climate change, erosion, storms

New data gathering techniques proving valuable

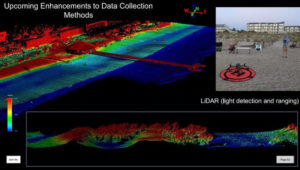

Different from past assessments of beach erosion, the Skidaway Institute of Oceanography’s analyses provide more comprehensive measurements done quarterly and after storm events rather than just annually.

The research team is bringing on new technology almost as soon as its available, said Alexander. Currently, the team carries out their projects through photogrammetry – using drones to take pictures of the island at different angles in order to create a digital surface model or elevation map – as well as LiDAR, an even more advanced way of measuring elevation using laser. This is the first project of its kind in the state of Georgia, looking at changes in beach behavior on such a fine scale, according to Alexander.

“We’re so proud of the data collection because it’s never been done before,” said Shawn Gillen, Tybee Island city manager. “It’s going to be really great info on deciding where and when to put sand on the beach.”

Latest on beach renourishment:Tybee Island Storm Risk Management Act gains U.S. Senate approval, heads to U.S. House

In the face of rising sea level and climate change, beach renourishment projects are trending more towards these natural fortifications — beach renourishment and dunes — rather than hard, man-made structures such as seawalls and rock groins, which can actually lead to more erosion, according to the NOAA.

Tybee Island is due for another beach renourishment in the next few years. The timing depends on the renewal of the federal authorization contract, which expires in 2024 and needs to be in place so the city can continue receiving federal funds for the costly projects. The Tybee Island Storm Risk Management Act, which would extend the contract another 50 years and is part of the larger Water Resources Development Act of 2022 (WRDA), is awaiting approval by the U.S. House.